Jerusalem by Jez Butterworth — Review

So when I heard it was being performed locally I was excited. In conjunction with Exeter's Northcott Theatre, Common Players are giving West Country audiences the chance to see Jerusalem in a series of open-air performances around Devon (we went to see it at Torre Abbey). Given the play's premise this seems appropriate: set in a West Country town, it is a paean to England past and present, its history, myths, identity, people and their relationships with the land and each other – complete with an actual chicken wandering through the audience (I was hoping to entice her upon my knee but evidently other laps looked more inviting).

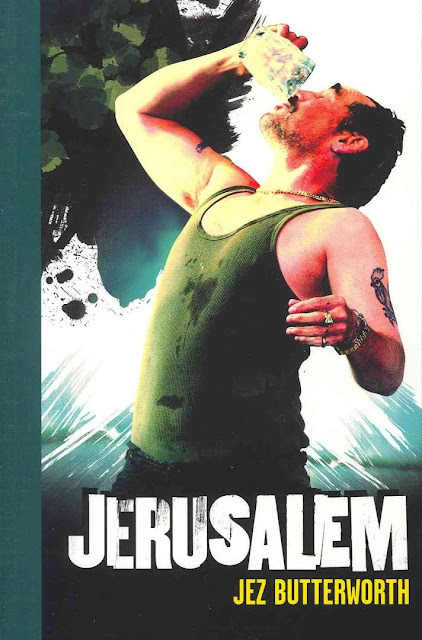

This was because of the main character, Johnny 'Rooster' Byron, who, all hairy armpits and sweaty vest, emerges from his caravan in the forest, cracks an egg into a pint glass of milk, chucks in a wrap of speed, stirs it with his fingers and downs it in one. Setting him up as an outsider, this gag-inducing act is also the hair of the dog: at a party the night before he was filmed smashing up his TV with a baseball bat – just the latest of a lifetime's hell-raising antics. An ex-daredevil biker who once jumped over buses and was declared clinically dead, Byron is now resident wild man of the woods, a Robin Hood/ Pied Piper figure towards whom the local disaffected youth gravitate. Byron's patch provides a place to escape – and also to access drugs, which Byron has in abundance. No wonder the council has threatened to bulldoze his abode.

The play also tries to imply, however, that he is more than a charismatic pisshead, that beneath the anti-social behaviour and unreliable biography – Byron mythologises himself as being gypsy-born with a black cape, a dagger and a full set of teeth – lies complexity. Falstaffian storyteller, philosopher, wise man, perhaps Byron even represents England itself? There is certainly ambiguity – and perhaps this is the point. A nation ill at ease with our own identity – how to celebrate St George's Day without it being high-jacked by the EDL? – we English are fascinated to see depictions of ourselves. And here there's a lot thrown in to the mix: Morris men, country fairs, giants, fairies, rave music, swearing, boozing, drugs. Then there are the names culled from ancient Greek and Shakespearean drama – Pea, Tanya, Phaedra and Troy– and the Blakeian references. Its title alluding to Blake's idea of the original, spiritual state of England, Jerusalem is grounded in a vision of England that endures. "Happy St George's Day! Now kiss my beggar arse, you puritans!" Rooster Byron yells. No one I know talks like that, yet the language evokes former times as well as pitching us in the present.

All of this was handled skilfully by the cast, who more than rose to the challenge of high expectation and delivered great comic performances – I laughed out loud several times. Gareth Evans' wannabe DJ Ginger, a character more fully rounded and nuanced than Byron, was particularly engaging, gently tolerant of and counteracting Byron's eccentricities with a light sardonic touch.

Nevertheless, despite attempting to cover many bases, the text remains unsatisfying. Those who prefer sympathetic characters, strong female roles and resolved endings won't find them here. Rooster is hard to warm to – if you came across him in a pub you'd give him a wide berth (and does the council boot him out or not? This is left moot). The implication is that Byron represents something profoundly substantial, perhaps all of us at some unconscious level, and maybe we would all like to flout social convention from time to time. But given the unsatisfactory nature of the play as a whole I find the character to be no more than an egocentric bullshitter (his supposed erudition turns out to be nothing more than facts gleaned from Trivial Pursuit cards).

Which leaves me scratching my head in bewilderment a bit. Much of the hype first time round probably had more to do with Mark Rylance's performance as the original Rooster Byron than the play itself. It was, by all accounts, magical. But my dad is a more interesting character than Byron – and a lot more pleasant to have a drink with, too. Maybe someone should write a play about him.

Comments

Post a Comment